This is Part 4 of a five-part series by Urban One, which outlines recommendations and proposals for improving the California/Los Angeles density bonus program. Part 1 focused on background, while Parts 2 through 5 include specific recommendations to improve the density bonus and affordable housing provision throughout the region.

With our previous proposals in Part 2 and Part 3 we’ve focused on modifications to the existing density bonus law. For this one, we go in a slightly different direction. We’re going to look at some recent specific plans in LA—one implemented, one currently in draft form—that, while not technically a part of the density bonus program, operate in a similar way.

These plans are largely dependent on capturing the increased land values that accompany “upzones”—that is, changes to zoning that allow for increased development potential within a neighborhood—and are not as applicable outside of this context. Upzones are a fairly common occurrence, however, so it’s worth exploring how we can make the most of them to increase equity and provide additional community resources. The affordable housing incentives in these plans can also be seen as a sort of “density bonus on steroids,” and so the connection between this and the proposal in Part 2 should become clear as we move along.

So with that background in mind, let’s move on to proposal 3!

Proposal: Capture value of increased development potential in upzoned neighborhoods.

Of the two plans we wanted to look at, the Cornfield Arroyo Seco Specific Plan (CASP) is probably most familiar to readers. CASP was adopted fairly recently and it includes a number of provisions and requirements related to unit density, floor-area ratio (FAR), commercial vs residential uses, etc., but for our purposes we’ll just focus on the affordable housing options discussed in the Zoning and Standards section.

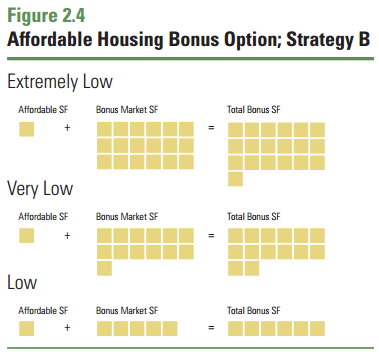

There are actually two options available to take advantage of the density bonus outlined in CASP, but one—Strategy B—seems much more viable from a developer’s perspective. (Note that we are not experts on CASP and it’s entirely possible that we’re misinterpreting the implementation process for Strategy A. There are also nuances we will deliberately overlook to simplify the explanation.) As mentioned above, this affordable housing option is something like a “density bonus on steroids,” allowing the developer to build up to 4.0 FAR in certain “Urban Village”-designated areas—a more than 150 percent increase over the base 1.5 FAR. This means that, with a share of its units set aside as affordable housing, a 50,000 square-foot (SF) plot of land could be developed up to 200,000 rather than 75,000 SF. That means more affordable and market-rate housing for local residents.

Specifics aside, the reason that neighborhoods like CASP can put exceptional requirements on new construction is that those requirements are coupled to significant increases in development potential. That development potential has financial value, and so while the city gives with one hand (upzoning) it takes with the other (additional development requirements). As long as the value of the upzoning exceeds the cost of those new requirements, everyone wins. The owners get a little bit more money—but not a windfall—and the community is able to capture most of the increase in value in the form of affordable housing, open space, transportation improvements, and other local amenities.

A similar program—the Exposition Corridor Transit Neighborhood Plan (ECTNP)— is underway in Phase II Expo station neighborhoods all the way to West LA. Like the CASP, the Expo Corridor plan includes a range of public benefits that must be provided in order for developers to build to the new maximum heights, FARs, etc. Also like the CASP, affordable housing is a major component of this specific plan.

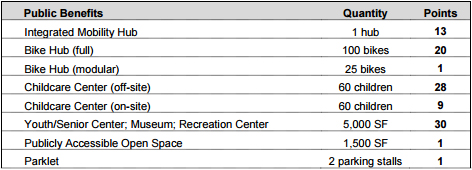

The ECTNP differs from CASP in that it seems more straightforward and easy to interpret. Rather than having a variety of paths and strategies for taking advantage of the new FAR limits, every developer in the Expo corridor neighborhoods must follow essentially the same path: First, all new developments are required to include some baseline set of public benefits, including basic streetscape improvements, unbundled or otherwise better-managed parking, open space, and so on—these are required to build anything, regardless of FAR. To receive an intermediate density bonus, developers must provide any of a number of more expensive public benefits, including extensive streetscape improvements, publicly-available open space, mobility hubs, and so on. The quantity of public benefits to be provided is determined by the extent of private development, with a simple point system in place to make the calculations easy for developers to understand and plan for. More development means more public benefits, which is a great strategy for getting local communities on board with new growth.

To receive the full density bonus, which can amount to as much as an 85 percent increase over the intermediate FAR limits, affordable housing must be provided. Twenty percent of all residential units must be affordable to low income residents (up to 80 percent of area median income), compared to up to 20 percent of pre-bonus units for traditional density bonus projects. In this respect, the requirement is more stringent than the citywide density bonus. Again, the value of the added development potential is what makes this policy workable. Why give away the added value for free, right?

As the city continues to evolve and new areas open up for rezoning and redevelopment, finding more ways to make the most of these value capture mechanisms—not just improving financial returns, but also making participation as straightforward and easy to understand as possible—should be a priority. It’s clear that city planners already have this in mind, and hopefully more attention can be brought to these plans, with more stakeholders working to make them as effective and streamlined as possible.

That’s a wrap on Part 4! We’ve saved the best for last in this series, so stay tuned for Part 5 of Building a Better Density Bonus! It involves a completely new approach to the density bonus that has the potential to dramatically reshape how we provide affordable housing in our city. It could also be a much more sustainable way to provide affordable housing, with a long-term growth strategy and permanent affordability restrictions rather than the limited-duration covenants in place for most subsidized housing available today. Coming soon!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

Note: It is not our intent that the ideas/recommendations included in this series be interpreted as ideal solutions to our city and state’s affordable housing problems. Rather, in the spirit of the LABC Institute’s recent report, we hope to foster engagement and debate about this important subject, and to begin the process of a transition toward more effective and efficient programs that better serve the needs of all LA residents—especially those with limited incomes who suffer the most from a lack of affordable housing. There are undoubtedly a variety of legal and procedural barriers to many of these ideas; some of those are in place for good reason, others may not be and should be reconsidered. Also please note that the ideas in this series are presented on behalf of Urban One and do not necessarily reflect to ideas, recommendations, or values of any other individual or organization.

We invite readers to share their comments and their own ideas for how we might improve the provision of affordable and market-rate homes, implementation ideas and tweaks to the ideas presented here, or case studies of similar successful programs in other cities and countries.