Last week we wrote about how Los Angeles isn’t building nearly enough housing to keep prices under control. Apparently, someone’s listening.

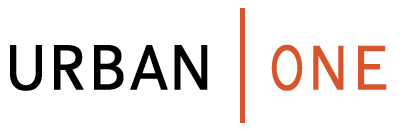

At the LA Business Council’s annual Housing, Transportation, and Jobs Summit this last Wednesday, Mayor Garcetti announced his goal to build 100,000 new housing units in the city by 2021, noting that the city is facing its worst affordability crisis since WWII and that we must do more to meet the growing demand for housing in the region. He identified several strategies for achieving this goal, including a stronger commitment to the city’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund, cutting red tape at the city, and pursuing CEQA reform at the state level.

It’s encouraging to see the Mayor acknowledging that the affordability crisis requires action on several fronts, not just increasing the amount spent on subsidized housing — undoubtedly a high priority — but also reducing impediments to private construction. The two goals are intimately related: the more cumbersome and costly it is to build new housing, the fewer homes will be built. The fewer homes that are built, the more pressure there is on the price of existing units, and the greater the differential between market-rate and subsidized housing. Those higher market-rate rents directly affect working and middle class families’ ability to afford decent housing, and they mean that deeper subsidies are required to support income-restricted housing — in other words, every dollar we invest in affordable housing doesn’t go quite as far.

On the affordable housing side, an effective housing policy should include a broad-based funding source such as property taxes (which everyone generally pays, including renters, since those costs are typically passed on by landlords). Right now, the burden of providing affordable housing is mostly borne by developers, which is acceptable to some degree but is neither equitable nor sufficient. Aside from being too small a source of funding, the cost of affordable housing set-asides in new developments — for example, requirements that 20% of new units be income-restricted — ultimately fall on the market-rate renters of those new units. If we break LA residents into three broad groups, 1) low- to middle-income renters, 2) middle- to upper-income renters, and 3) middle- to upper-income homeowners, we can see that Group 2, the middle group, is bearing most of the cost of providing housing for Group 1. Despite their greater income and wealth, Group 3, the homeowners, do not contribute to the cost of affordable housing under this scheme. A fairer, more equitable system is required.

On the market side, as Mayor Garcetti would undoubtedly agree, building 100,000 new housing units can’t happen without the private sector shouldering the vast majority of the workload — the public and non-profit sectors simply lack the funding, expertise (in some cases), and capacity. What city leaders must be wary of is the tendency to want to fund public and non-profit development by taking a cut of private development profits. While easy to sell politically, the practical results can be disastrous for housing affordability if those extractions grow too extreme. There are a few reasons this is the case:

- First, the construction/development market is like any other investment market where investors seek the best return for the least risk. The more we depend on developers to fund all of the perks that we’ve come to expect from new construction — park space, bike lanes, affordable housing, community centers, etc. — the worse the returns for investors, and the more likely they are to look elsewhere for places to invest their money. Even when they keep their money in real estate, they’re more likely to turn to high-profit luxury developments to ensure a competitive return. We shoot ourselves in the foot when we encourage this type of behavior. Developers have a responsibility to the communities in which they build, but their need for competitive profits has to be balanced with those responsibilities

- Second, private construction accounts for the vast majority of residential construction in the country. According to the Census Bureau, the seasonally-adjusted annual value of private residential construction in the U.S. was $349 billion. Public residential construction over this same period was valued at less than $6 billion, less than 2 percent of the private amount. Additionally, only 1/3 of subsidized “social” housing was built by non-profits. The clear takeaway here is that harm done to the private sector — even relatively small reductions in productivity — can swamp whatever gains are made on the public/non-profit side when funds are shifted from the former to the latter.

To be clear, this isn’t an argument that developers should be given free reign. Regulations and public benefits are generally in place for good reasons, and funding aimed at assisting our most vulnerable populations is essential. However, when additional costs are imposed (linkage fees, for example) they should be directly tied to offsetting measures that can expedite the development process and reduce costs in other ways. Examples include expanding the realm of development that can be performed “by-right” (that is, without the need for discretionary approval from a planning commission or other deliberative body); reducing or eliminating parking minimums that vastly increase project costs (and tend to be underutilized besides); and opening up more of the city’s land to multi-family development, limiting the run-up in land values that occurs when only a tiny share of the city can legally grow any denser.

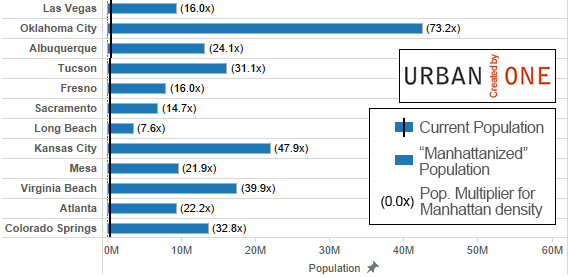

These recommendations are by no means new, but with a mounting affordability crisis there may now be a real commitment to charting a new course. As noted last week, our current rate of housing construction has us tied with San Francisco’s 15-year average, and that is clearly not a city we want to emulate if we hope to keep costs under control. Liberalizing development policy can help us achieve our goal of building 100,000 new homes by 2021, and if done right, it can also leave us with more money for supportive and income-restricted housing, more affordable market-rate housing, and more rational development that’s geared toward a healthier, more sustainable future.